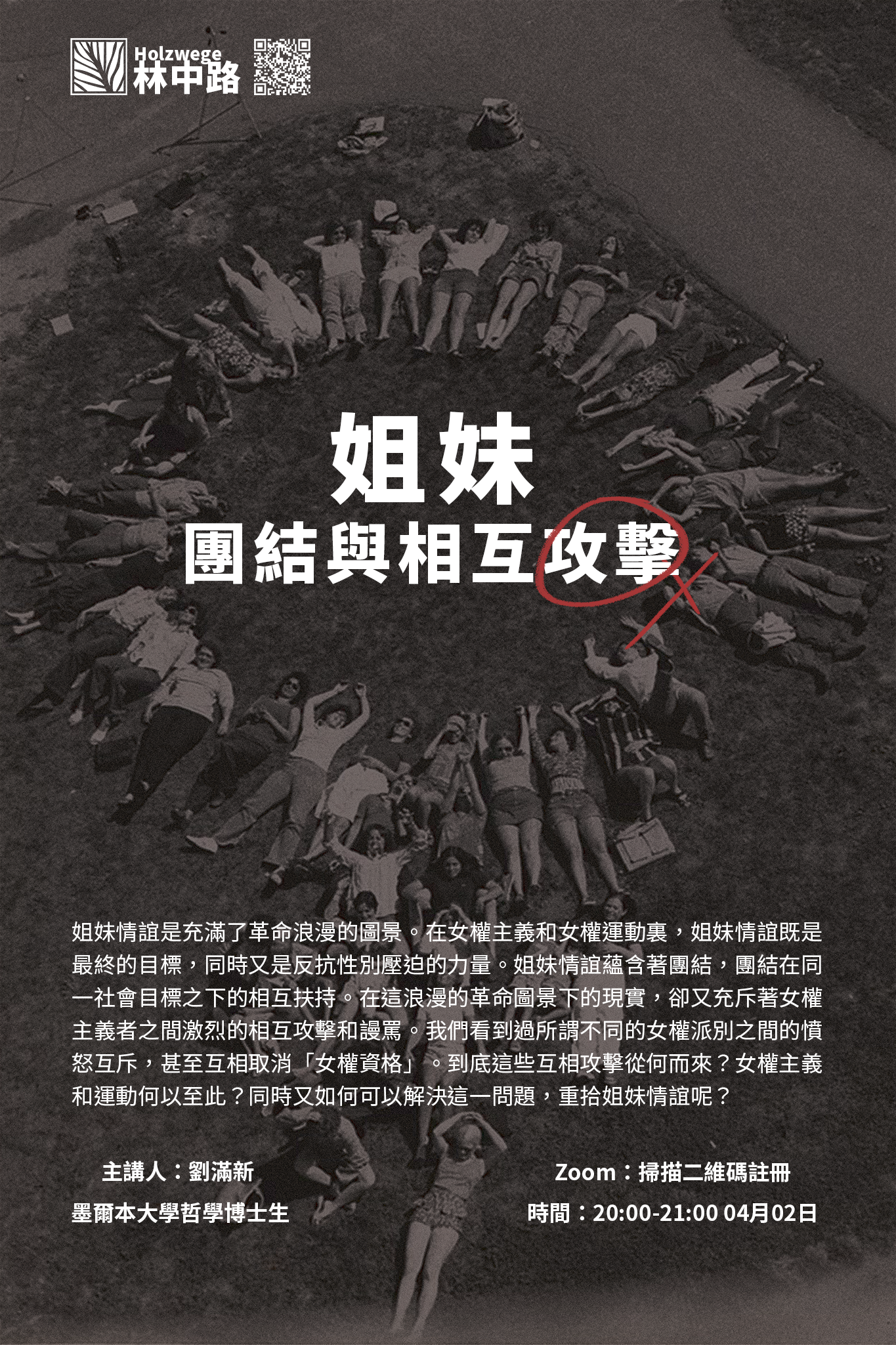

講座導讀 · Trashing: The Dark Side of Sisterhood 姐妹情誼的暗面

中文導語

這篇文章是美國女權主義者喬·弗里曼1976年發表在Ms雜誌的一篇文章,剛發佈就引起了很大反響,很多讀者的反饋都是關於她們自己被「trashing」的故事。

喬·弗里曼講述了其在芝加哥被女性解放組織邊緣化並且從女性運動中除名的經歷。作者通過其自身經歷向讀者解釋了「trashing」的不同定義,「transhing」不僅可以發生在私人場合裏,也可以發生在小組對話中;可以是當面發生的,也可以是在背後講述的,是通過譴責和排斥讓個體覺得被完全邊緣化的行為,會讓人完全懷疑自己對現實的認知和自己存在的意義。

在女性主義運動這個特定情境下,被「trashing」會讓個體懷疑自己在運動中是否能夠提供幫助、發揮作用,自己的存在是不是完全沒有意義甚至是有害的。

作者提到,自己因為被「transhing」度過了很長一段自我懷疑、完全把錯位內在化的痛苦日子。直到1970年,弗里曼在紐約遇到了其他幾位女性主義者,她們在討論了女性主義運動的過程裏發現,她們都有過被「trashing」的經歷。

由此弗里曼開始反思這段經歷。她發現,被「trashing」更像是一個嚴重的社會疾病,而它的嚴重後果躲在了所謂「sisterhood」之中,因而長久以來被隱藏。在女性主義運動的新價值觀裏,每一位女性都是一名姐妹,每一位女性都是可以被接受的,可是弗里曼在這項運動中很顯然不是被接受的一方,反而,「sisterhood」像是一把刀切斷了她和別的女性的聯繫以及她對自我的實際認知。

她提出,「trashing」不僅對個人具有破壞性,更是一種非常強大的社會控制工具。在這種情況下,女性們不會效仿那些受到攻擊的品質和風格,以免同樣的命運 (trashing) 降臨到她們身上。

其實,這並不只是女性運動的特點:利用社會壓力來誘導對個性的順從和不容忍,是美國社會特有的現象。主要問題也不是為什麼女性運動會施加如此強大的壓力來迫使女性遵守狹隘的標準,而是這些標準到底是什麼。這些標準披着革命和女權主義的花言巧語,但潛藏其下的卻是一些關於女性刻板角色的陳腐觀念。

不僅如此,女性運動中許多試圖想要分享自己的技能的女性遭受抨擊的原因在於,她們知道了很多別人不知道的事情。弗里曼認為,該運動對平等主義的崇拜是如此強烈,以至於她們已經與一成不變相混淆了。

由此,弗里曼不僅解釋被被「trashing」的不同女性主義者類型,還解釋了其背後的根本原因——我們往往對其他女權主義者和整個運動所達到的目標期望很高,因此期望很難被完全滿足。我們還沒有學會將我們對於姐妹亦或自己的要求放到現實裏,因此會產生憤怒情緒。

而憤怒是壓迫合乎邏輯的藉口,它需要一個出口。但在現實的社會環境下對於男性的攻擊「不明智」,因而這種憤怒被轉移到羣體內部。即所謂的:男人遙不可及,系統大而模糊,姐妹卻近在咫尺——攻擊其他女權主義者比攻擊無定型的社會機構更容易。

最後,弗里曼呼籲大家停止對其他女性主義者的苛刻要求,停止尋找內在敵人,開始面對真正的外敵。

英文原文

TRASHING: The Dark Side of Sisterhood

by Joreen

This article was written for Ms. magazine and published in the April 1976 issue, pp. 49-51, 92-98. It evoked more letters from readers than any article previously published in Ms., all but a few relating their own experiences of being trashed. Quite a few of these were published in a subsequent issue of Ms.

It's been a long time since I was trashed. I was one of the first in the country, perhaps the first in Chicago, to have my character, my commitment, and my very self attacked in such a way by Movement women that it left me torn in little pieces and unable to function. It took me years to recover, and even today the wounds have not entirely healed. Thus I hang around the fringes of the Movement, feeding off it because I need it, but too fearful to plunge once more into its midst. I don't even know what I am afraid of. I keep telling myself there's no reason why it should happen again -- if I am cautious -- yet in the back of my head there is a pervasive, irrational certainty that says if I stick my neck out, it will once again be a lightning rod for hostility.

First of all, so much dirty linen is being publicly exposed that I doubt that what I have to reveal will add much to the pile. To those women who have been active in the Movement, it is not even a revelation. Second, I have been watching for years with increasing dismay as the Movement consciously destroys anyone within it who stands out in any way. I had long hoped that this self-destructive tendency would wither away with time and experience. Thus I sympathized with, supported, but did not speak out about, the many women whose talents have been lost to the Movement because their attempts to use them had been met with hostility. Conversations with friends in Boston, Los Angeles, and Berkeley who have been trashed as recently as 1975 have convinced me that the Movement has not learned from its unexamined experience Instead, trashing has reached epidemic proportions. Perhaps taking it out of the closet will clear the air.

What is "trashing," this colloquial term that expresses so much, yet explains so little? It is not disagreement; it is not conflict; it is not opposition. These are perfectly ordinary phenomena which, when engaged in mutually, honestly, and not excessively, are necessary to keep an organism or organization healthy and active. Trashing is a particularly vicious form of character assassination which amounts to psychological rape. It is manipulative, dishonest, and excessive. It is occasionally disguised by the rhetoric of honest conflict, or covered up by denying that any disapproval exists at all. But it is not done to expose disagreements or resolve differences. It is done to disparage and destroy.

The means vary. Trashing can be done privately or in a group situation; to one's face or behind one's back; through ostracism or open denunciation. The trasher may give you false reports of what (horrible things) others think of you; tell your friends false stories of what you think of them; interpret whatever you say or do in the most negative light; project unrealistic expectations on you so that when you fail to meet them, you become a "legitimate" target for anger; deny your perceptions of reality; or pretend you don't exist at all. Trashing may even be thinly veiled by the newest group techniques of criticism/self-criticism, mediation, and therapy. Whatever methods are used, trashing involves a violation of one's integrity, a declaration of one's worthlessness, and an impugning of one's motives In effect, what is attacked is not one's actions, or one's ideas, but one's self.

This attack is accomplished by making you feel that your very existence is inimical to the Movement and that nothing can change this short of ceasing to exist. These feelings are reinforced when you are isolated from your friends as they become convinced that their association with-you is similarly inimical to the Movement and to themselves. Any support of you will taint them. Eventually all your colleagues join in a chorus of condemnation which cannot be silenced, and you are reduced to a mere parody of your previous self.

It took three trashings to convince me to drop out. Finally, at the end of 1969, I felt psychologically mangled to the point where I knew I couldn't go on. Until then I interpreted my experiences as due to personality conflicts or political disagreements which I could rectify with time and effort. But the harder I tried, the worse things got, until I was finally forced to face the incomprehensible reality that the problem was not what I did, but what I was.

This was communicated so subtly that I never could get anyone to talk about it. There were no big confrontations, just many little slights. Each by itself was insignificant; but added one to another they were like a thousand cuts with a whip. Step by step I was ostracized: if a collective article was written, my attempts to contribute were ignored; if I wrote an article, no one would read it; when I spoke in meetings, everyone would listen politely, and then take up the discussion as though I hadn't said anything; meeting dates were changed without my being told; when it was my turn to coordinate a work project, no one would help; when I didn't receive mailings, and discovered that my name was not on the mailing list, I was told I had just looked in the wrong place. My group once decided on joint fund-raising efforts to send people to a conference until I said I wanted to go, and then it was decided that everyone was on her own (in fairness, one member did call me afterward to contribute $5 to my fare, provided that I not tell anyone. She was trashed a few years later).

My response to this was bewilderment. I felt as though I were wandering blindfolded in a field I full of sharp objects and deep holes while being reassured that I could see perfectly and was in a smooth, grassy pasture. It was is if I had unwittingly entered a new society, one operating by rules of which I wasn't aware, and couldn't know. When I tried to get my group(s) to discuss what I thought was happening to me, they either denied my perception of reality by saying nothing was out of the ordinary, or dismissed the incidents as trivial (which individually they were). One woman, in private phone conversations, did admit that I was being poorly treated. But she never supported me publicly, and admitted quite frankly that it was because she feared to lose the group's approval. She too was trashed in another group.

Month after month the message was pounded in: get out, the Movement was saying: Get Out, Get Out! One day I found myself confessing to my roommate that I didn't think I existed; that I was a figment of my own imagination. That's when I knew it was time to leave. My departure was very quiet. I told two people, and stopped going to the Women's Center. The response convinced me that I had read the message correctly. No one called, no one sent me any mailings, no reaction came back through the grapevine. Half my life had been voided, and no one was aware of it but me. Three months later word drifted back that I had been denounced by the Chicago Women's Liberation Union, founded after I dropped out of the Movement, for allowing myself to be quoted in a recent news article without their permission. That was all.

The worst of it was that I really didn't know why I was so deeply affected. I had survived growing up in a very conservative, conformist, sexist suburb where my right to my own identity was constantly under assault. The need to defend my right to be myself made me tougher, not tattered. My thickening skin was further annealed by my experiences in other political organizations and movements, where I learned the use of rhetoric and argument as weapons in political struggle, and how to spot personality conflicts masquerading as political ones. Such conflicts were usually articulated impersonally, as attacks on one's ideas, and while they may not have been productive, they were not as destructive as those that I later saw in the feminist movement. One can rethink one's ideas as a result of their being attacked. It's much harder to rethink one's personality. Character assassination was occasionally used, but it was not considered legitimate, and thus was limited in both extent and effectiveness. As people's actions counted more than their personalities, such attacks would not so readily result in isolation. When they were employed, they only rarely got under one's skin.

But the feminist movement got under mine. For the first time in my life, I found myself believing all the horrible things people said about me. When I was treated like shit, I interpreted it to mean that I was shit. My reaction unnerved me as much as my experience. Having survived so much unscathed, why should I now succumb? The answer took me years to arrive at. It is a personally painful one because it admits of a vulnerability I thought I had escaped. I had survived my youth because I had never given anyone or any group the right to judge me. That right I had reserved to myself. But the Movement seduced me by its sweet promise of sisterhood. It claimed to provide a haven from the ravages of a sexist society; a place where one would be understood. it was my very need for feminism and feminists that made me vulnerable. I gave the movement the right to judge me because I trusted it. And when it judged me worthless, I accepted that judgment.

For at least six months I lived in a kind of numb despair, completely internalizing my failure as a personal one. In June, 1970, I found myself in New York coincidentally with several feminists from four different cities. We gathered one night for a general discussion on the state of the Movement, and instead found ourselves discussing what had happened to us. We had two things in common; all of us had Movement-wide reputations, and all had been trashed. Anselma Dell'Olio read us a speech on "Divisiveness and Self-Destruction in the Women's Movement" she had recently given at the Congress To Unite Women (sic) as a result of her own trashing.

"I learned ... years ago that women had always been divided against one another, self-destructive and filled with impotent rage. I thought the Movement would change all that. I never dreamed that I would see the day when this rage, masquerading as a pseudo-egalitarian radicalism [would be used within the Movement to strike down sisters singled out

"I am referring ... to the personal attacks, both overt and insidious, to which women in the Movement who had painfully managed any degree of achievement have been subjected. These attacks take different forms. The most common and pervasive is character assassination: the attempt to undermine and destroy belief in the integrity of the individual under attack. Another form is the 'purge.' The ultimate tactic is to isolate her. . . .

"And who do they attack? Generally two categories. . . Achievement or accomplishment of any kind would seem to be the worst crime: ... do anything . . . that every other woman secretly or otherwise feels she could do just as well -- and ... you're in for it. If then ... you are assertive, have what is generally described as a 'forceful personality/ if ... you do not fit the conventional stereotype of a 'feminine' woman, ... it's all over.

"If you are in the first category (an achiever), You are immediately labeled a thrill-seeking opportunist, a ruthless mercenary, out to make her fame and fortune over the dead bodies of selfless sisters who have buried their abilities and sacrificed their ambitions for the greater glory of Feminism. Productivity seems to be the major crime -- but if you have the misfortune of being outspoken and articulate, you are also accused of being power-mad, elitist, fascist, and finally the worst epithet of all: a male-identifier. Aaaarrrrggg!"

As I listened to her, a great feeling of relief washed over me. It was my experience she was describing. If I was crazy, I wasn't the only one. Our talk continued late into the evening. When we left, we sardonically dubbed ourselves the "feminist refugees" and agreed to meet sometime again. We never did. Instead we each slipped back into our own isolation, and dealt with the problem only on a personal level. The result was that most of the women at that meeting dropped out as I had done. Two ended up in the hospital with nervous breakdowns. Although all remained dedicated feminists, none have really contributed their talents to the Movement as they might have. Though we never met again, our numbers grew as the disease of self-destructiveness slowly engulfed the Movement.

Over the years I have talked with many women who have been trashed. Like a cancer, the attacks spread from those who had reputations to those who were merely strong; from those who were active to those who merely had ideas; from those who stood out as individuals to those who failed to conform rapidly enough to the twists and turns of the changing line. With each new story, my conviction grew that trashing was not an individual problem brought on by individual actions; nor was it a result of political conflicts between those of differing ideas, It was a social disease.

The disease has been ignored so long because it is frequently masked under the rhetoric of sisterhood. In my own case, the ethic of sisterhood prevented a recognition of my ostracism. The new values of the Movement said that every woman was a sister, every woman was acceptable. I clearly was not. Yet no one could admit that I was not acceptable without admitting that they were not being sisters. It was easier to deny the reality of my unacceptability. With other trashings, sisterhood has been used as the knife rather than the cover-up. A vague standard of sisterly behavior is set up by anonymous judges who then condemn those who do not meet their standards. As long as the standard is vague and utopian, it can never be met. But it can be shifted with circumstances to exclude those not desired as sisters. Thus Ti-Grace Atkinson's memorable adage that "sisterhood is powerful: it kills sisters" is reaffirmed again and again.

Trashing is not only destructive to the individuals involved, but serves as a very powerful tool of social control. The qualities and styles which are attacked become examples other women learn not to follow -- lest the same fate befall them. This is not a characteristic peculiar to the Women's Movement, or even to women. The use of social pressures to induce conformity and intolerance for individuality is endemic to American society. The relevant question is not why the Movement exerts such strong pressures to conform to a narrow standard, but what standard does it pressure women to conform to.

This standard is clothed in the rhetoric of revolution and feminism. But underneath are some very traditional ideas about women's proper roles. I have observed that two different types of women are trashed. The first is the one described by Anselma Dell'Olio -- the achiever and/or the assertive woman, the one to whom the epithet "male-identified" is commonly applied. This kind of woman has always been put down by our society with epithets ranging from "unladylike" to "castrating bitch." The primary reason there have been so few "great women ______" is not merely that greatness has been undeveloped or unrecognized, but that women exhibiting potential for achievement are punished by both women and men. The "fear of success" is quite rational when one knows that the consequence of achievement is hostility and not praise.

Not only has the Movement failed to overcome this traditional socialization, but some women have taken it to new extremes. To do something significant, to be recognized, to achieve, is to imply that one is "making it off other women's oppression" or that one thinks oneself better than other women. Though few women may think this, too many remain silent while the others unsheathe their claws. The quest for "leaderlessness" that the Movement so prizes has more frequently become an attempt to tear down those women who show leadership qualities, than to develop such qualities in those who don't. Many women who have tried to share their skills have been trashed for asserting that they know something others don't. The Movement's worship of egalitarianism is so strong that it has become confused with sameness. Women who remind us that we are not all the same are trashed because their differentness is interpreted as meaning we are not all equal.

Consequently the Movement makes the wrong demands from the achievers within it. It asks for guilt and atonement rather than acknowledgment and responsibility. Women who have benefitted personally from the Movement's existence do owe it more than gratitude. But that debt is not called in by trashing. Trashing only discourages other women from trying to break free of their traditional shackles.

The other kind of woman commonly trashed is one I would never have suspected. The values of the Movement favor women who are very supportive and self-effacing; those who are constantly attending to others' personal problems; the women who play the mother role very well. Yet a surprising number of such women have been trashed. Ironically their very ability to play this role is resented and creates an image of power which their associates find threatening. Some older women who consciously reject the mother role are expected to play it because they "look the part" -- and are trashed when they refuse. Other women who willingly play it find they engender expectations which they eventually cannot meet, No one can be "everything to everybody," so when these women find themselves having to say no in order to conserve a little of their own time and energy for themselves or to tend to the political business of a group, they are perceived as rejecting and treated with anger. Real mothers of course can afford some anger from their children because they maintain a high degree of physical and financial control over them. Even women in the "helping" professions occupying surrogate mother roles have resources with which to control their clients' anger. But when one is a "mother" to one's peers, this is not a possibility. If the demands become unrealistic, one either retreats, or is trashed.

The trashing of both these groups has common roots in traditional roles. Among women there are two roles perceived as permissible: the "helper" and the "helped." Most women are trained to act out one or the other at different times. Despite consciousness-raising and an intense scrutiny of our own socialization, many of us have not liberated ourselves from playing these roles, nor from our expectations that others will do so. Those who deviate from these roles -- the achievers -- are punished for doing so, as are those who fail to meet the group's expectations.

Although only a few women actually engage in trashing, the blame for allowing it to continue rests with us all. Once under attack, there is little a woman can do to defend herself because she is by definition always wrong. But there is a great deal that those who are watching can do to prevent her from being isolated and ultimately destroyed. Trashing only works well when its victims are alone, because the essence of trashing is to isolate a person and attribute a group's problems to her. Support from others cracks this facade and deprives the trashers of their audience. It turns a rout into a struggle. Many attacks have been forestalled by the refusal of associates to let themselves be intimidated into silence out of fear that they would be next. Other attackers have been forced to clarify their complaints to the point where they can be rationally dealt with.

There is, of course, a fine line between trashing and political struggle, between character assassination and legitimate objections to undesirable behavior. Discerning the difference takes effort. Here are some pointers to follow. Trashing involves heavy use of the verb "to be" and only a light use of the verb "to do." It is what one is and not what one does that is objected to, and these objections cannot be easily phrased in terms of specific undesirable behaviors. Trashers also tend to use nouns and adjectives of a vague and general sort to express their objections to a particular person. These terms carry a negative connotation, but don't really tell you what's wrong. That is left to your imagination. Those being trashed can do nothing right. Because they are bad, their motives are bad, and hence their actions are always bad. There is no making up for past mistakes, because these are perceived as symptoms and not mistakes.

The acid test, however, comes when one tries to defend a person under attack, especially when she's not there, If such a defense is taken seriously, and some concern expressed for hearing all sides and gathering all evidence, trashing is probably not occurring. But if your defense is dismissed with an oft-hand "How can you defend her?"; if you become tainted with suspicion by attempting such a defense; if she is in fact indefensible, you should take a closer look at those making the accusations. There is more going on than simple disagreement.

As trashing has become more prevalent, I have become more puzzled by the question of why. What is it about the Women's Movement that supports and even encourages self-destruction? How can we on the one hand talk about encouraging women to develop their own individual potential and on the other smash those among us who do just that? Why do we damn our sexist society for the damage it does to women, and then damn those women who do not appear as severely damaged by it? Why has consciousness-raising not raised our consciousness about trashing?

The obvious answer is to root it in our oppression as women, and the group self-hate which results from our being raised to believe that women are not worth very much. Yet such an answer is far too facile; it obscures the fact that trashing does not occur randomly. Not all women or women's organizations trash, at least not to the same extent. It is much more prevalent among those who call themselves radical than among those who don't; among those who stress personal changes than among those who stress institutional ones; among those who can see no victories short of revolution than among those who can be satisfied with smaller successes; and among those in groups with vague goals than those in groups with concrete ones.

I doubt that there is any single explanation to trashing; it is more likely due to varying combinations of circumstances which are not always apparent even to those experiencing them. But from the stories I've heard, and the groups I've watched, what has impressed me most is how traditional it is. There is nothing new about discouraging women from stepping out of place by the use of psychological manipulation. This is one of the things that have kept women down for years; it is one thing that feminism was supposed to liberate us from. Yet, instead of an alternative culture with alternative values, we have created alternative means of enforcing the traditional culture and values. Only the name has changed; the results are the same.

While the tactics are traditional, the virulence is not. I have never seen women get as angry at other women as they do in the Movement. In part this is because our expectations of other feminists and the Movement in general are very high, and thus difficult to meet. We have not yet learned to be realistic in our demands on our sisters or ourselves. It is also because other feminists are available as targets for rage.

Rage is a logical result of oppression. It demands an outlet. Because most women are surrounded by men whom they have learned it is not wise to attack, their rage is often turned inward. The Movement is teaching women to stop this process, but in many instances it has not provided alternative targets. While the men are distant, and the "system" too big and vague, one's "sisters" are close at hand. Attacking other feminists is easier and the results can be more quickly seen than by attacking amorphous social institutions. People are hurt; they leave. One can feel the sense of power that comes from having "done something." Trying to change an entire society is a very slow, frustrating process in which gains are incremental, rewards diffuse, and setbacks frequent. It is not a coincidence that trashing occurs most often and most viciously by those feminists who see the least value in small, impersonal changes and thus often find themselves unable to act against specific institutions.

The Movement's emphasis on "the personal is political" has made it easier for trashing to flourish. We began by deriving some of our political ideas from our analysis of our personal lives. This legitimated for many the idea that the Movement could tell us what kind of people we ought to be, and by extension what kind of personalities we ought to have. As no boundaries were drawn to define the limits of such demands, it was difficult to preclude abuses. Many groups have sought to remold the lives and minds of their members, and some have trashed those who resisted. Trashing is also a way of acting out the competitiveness that pervades our society, but in a manner that reflects the feelings of incompetence that trashers exhibit. Instead of trying to prove one is better than anyone else, one proves someone else is worse. This can provide the same sense of superiority that traditional competition does, but without the risks involved. At best the object of one's ire is put to public shame, at worst one's own position is safe within the shrouds of righteous indignation, Frankly, if we are going to have competition in the Movement, I prefer the old-fashioned kind. Such competitiveness has its costs, but there are also some collective benefits from the achievements the competitors make while trying to outdo each other. With trashing there are no beneficiaries. Ultimately everyone loses.

To support women charged with subverting the Movement or undermining their group takes courage, as it requires us to stick our necks out. But the collective cost of allowing trashing to go on as long and as extensively as we have is enormous. We have already lost some of the most creative minds and dedicated activists in the Movement. More importantly, we have discouraged many feminists from stepping out, out of fear that they, too, would be trashed. We have not provided a supportive environment for everyone to develop their individual potential, or in which to gather strength for the battles with the sexist institutions we must meet each day. A Movement that once burst with energy, enthusiasm, and creativity has become bogged down in basic survival -- survival from each other. Isn't it time we stopped looking for enemies within and began to attack the real enemy without? The author would like to thank Linda, Maxine, and Beverly for their helpful suggestions in the revision of this paper.

Freeman, J., n.d. Trashing: The Dark Side of Sisterhood. [online] Jofreeman.com. Available at: <https://www.jofreeman.com/joreen/trashing.htm> [Accessed 29 March 2022].

喜欢我的作品吗?别忘了给予支持与赞赏,让我知道在创作的路上有你陪伴,一起延续这份热忱!

- 来自作者

- 相关推荐