人生意义的是与不是(1)

Hi Tim,

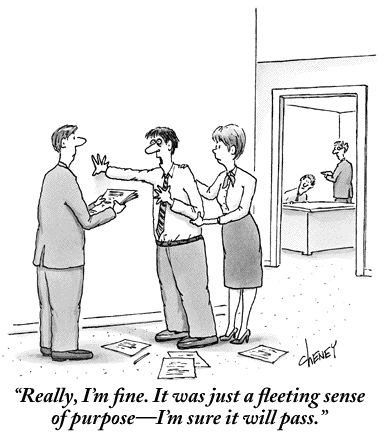

I’ve been thinking about ‘meaning’. I’ve been looking at job ads and many organisations say that they have a purpose, or that they allow you to ‘make an impact’. This is different from just saying that they just have goals. Philosophically speaking, to say that one has a purpose, there must be pre-existing assumptions for what that purpose is, what constitutes the purpose. In other words, it necessarily implies something deeper. Unfortunately, for these organisations, a purpose is merely equivalent to a set of goals. These organisations are very skilled at making their ‘mission statement’ sound like something inherently valuable, without any justification. This got me thinking: what is ‘meaning’ or ‘purpose’? In thinking about this question, I want to first explore what meaning is not, then give my own argument for what meaning is.

我最近看了很多招聘广告。很多都说"我们的工作很有意义"。可是"意义"是什么东西? 很多时候,公司所说的“意义”无非就是一些目标罢了。从哲学上来看,这似乎跟"意义"的意思不同。我想试一下用哲学的角度讨论意义。

A common starting point prevalent in human society is one’s contribution to the ‘progress’ of humanity. So it seems we have to first explain the concept of ‘progress’. In the worldview of the Hegelian and Marxist philosophies, human history is deemed to be a progression in stages, e.g. from feudalism to capitalism to socialism. More broadly, Western civilisation since the Enlightenment has believed in the role of reason and scientific thinking in the supposed progress of humanity. This is reflected everywhere in our society, perhaps none so blatant than the Olympic motto (or slogan) of citius, altius, fortius (faster, higher, stronger). The fact is, whether or not you are a conservative or progressive, you’d believe in the power of progress (in whichever direction) in achieving your ideal world. Now, naturally, one would ask, where does ‘progress’ lead to? I think there are three possibilities.

很多人把意义和进步/发展关联在一起:意义是以发展为基础的。比如马克思主义就认为人类的历史就是从封建制度发展到资本主义到共产主义的过程。西方文明从启蒙运动之后也一直深信理性和科学能够发展社会。一个例子是奥林匹亚精神:跟高更快更强。不管你是进步派还是保守派,你都得认为社会需要发展(尽管方向不同)。有一个问题就是:发展到哪里呢?我认为有三种可能。

When people speak of progress, we often presuppose that there be a finite progression leading up to a destination. I call this idea 'ultimate utopia'. For Marxists, the ultimate utopia is communism. For the religious, it’s concepts like ‘the promised land’. For the ancient Chinese, it’s the concept of the Great Unity, where everyone and everything is at peace with each other. For the utilitarians, it's a state in which everyone's utility is maximised. What I want to discuss here is: is this concept of progress possible? This is a question involving complex social, economic and political considerations, and I don’t want to claim that I know enough to answer it. But I can provide some resistance to the idea of an ultimate utopia by asking this: what if some people just want to be better off than others, as they get (perverse, sadistic) pleasure from it? These people seem to exist; and if so, human nature determines that we cannot live in a society e.g. where everyone's utility is maximised or where everyone is at peace with each other. Hence the very idea of an ultimate utopia seems to be a paradox.

第一种对发展的理解:人类社会最终会发展到一个完美的状态。我把它称为‘乌托邦的最终形态’。对于马克思主义者来说,这是共产主义。对于基督教信徒,这是天堂。对于古代中国哲学家,这是“天下为公”。对于功利主义者,这是当每个人的效益都被最大化的世界。人类有可能到达这种状态吗?我当然不知道。但是我可以可出一些反对的理由。如果一些人想要“出人头地”,也就是说他们想比别人活得更好,他们的快乐的来源是别人的痛苦。那么在一个乌托邦里这些人不会最大化其效益或者达到天下为公。所以这种形态的乌托邦的概念是自相矛盾的。

There can be an alternative interpretation of utopia. I call it 'limited utopia'. The idea is that human nature has imposed certain constraints, such as the aforementioned sadistic tendencies, on the kinds of society we can realistically and sustainably have. Limited utopias are the best societies we can build given these constraints. Whereas ultimate utopia can be thought of as the global maximum of human society, limited utopia can be thought of as the local maximum; and whereas ultimate utopia concerns what is logically possible, limited utopia concerns what is practically possible. I think this limited utopia is entirely possible.

另外一种可能性是“乌托邦的有限形态”。人类社会可能存在一种(或多种)"局部最优解"。也就是说,考虑到人本身的限制(比如喜欢出人头地),我们能不能达到一种社会上最好的状态?在这里我们考虑的是现实的可能性,而不是逻辑上的可能性。我觉得这是有可能的。

In This Life, Martin Hagglund provided a moderate form of socialism, where a society is organised such that people's labour is appropriately valued, rather than being valued by some capitalistic forces. This, Hagglund argues, allows people to 'fully own their time' and be responsible for the choices that they make, and thus makes people's lives meaningful. This is an example of a limited utopia which does not want all boring work to be eliminated. As Hagglund rightly acknowledges, socialism does not eradicate boring work but instead makes boring work (and all work) valued for what it's worth. An example: you work as a carer for the elderly for an hour, and under a capitalist society, you get $30. This might be the same as what leaflet senders get for doing an hour of their work. You are valued the same for doing either (even though they clearly don't have the same value). Under a socialist society, the meaning of your work is not measured in monetary terms, because you don't need to work for a living. You give it as much meaning as you want, considering how much contribution you actually make to the society and people you care about. This version of socialism recognises the imperfection of humanity, i.e. that there needs to be some boring work to do, and that's a result of human nature. To conclude, meaning does not depend on an ultimate-utopia view of progress and may depend on a limited-utopia view of progress, examplified by Hagglund's theory in This Life.

Hagglund的书This Life是一个例子。他给出了一种温和的社会主义,让人能够对自己的时间和选择负责人,让人的劳动正确地被评价。在资本主义里,你在老人院照顾老人和做派传单的得到的钱可能是一样的。你们的价值是一样的。在社会主义里,你可以对你的工作的意义做出自己的判断,因为你不需要为了生存而工作。你可以对自己对社会和你在意的人所做出的贡献有自己的评价。这种社会主义承认了人的不完美,即人类社会一定是有无聊的工作的。可是给了你一个自己选择、为时间负责任的空间。所以这是一种乌托邦的有限形态。

Another possible argument is to base meaning on the idea of infinite progress, that we can forever advance the society to no end. A reply to this argument comes from our physical understanding of the world. Our best theories in physics tell us that the universe is going to end someday (though there are disagreements). If so, then progress will have to end one day as the universe ends. Perhaps we need not go that far. There are dangers in the near future, like nuclear warfare, singularity, that could lead to the demise of humanity. Going further, are we going to have the technology to flee this galaxy when it inevitably becomes uninhabitable? Overall, in my discussion so far, I hope to have pointed out the falsity of some beliefs that I think many have implicitly endorsed, that meaning comes from the possibility of an ultimate utopia or from the infinite progress of society. I may add that this issue is so detached in our daily lives (or so frightening to think about) that most people simply don’t think much about it, but nevertheless act according to those beliefs. We can see that in eulogies of great people, as we often hear things like 'so-and-so has their live to [insert cause], contributing to the progress of humanity…'

最后一种可能性是无限的发展:人类社会的发展没有尽头。我们可以从物理的角度回答这种可能性:1)宇宙最后会被终结;2)人类能发展出技术逃离太阳系吗?3)在不远的未来,我们面临很多存在危机,如核武器战争、极点。这些困难可能是人类发展无法克服的。总结:我指出并否认了我认为很多人潜意识里认可的对意义的定义,i) 意义是基于于一个对乌托邦的最终形态的理解;2)意义是基于无限的发展。大多数人不会去想这些事情。不过他们在人生里做出的选择其实就是根据这些对意义的定义的。我们可以从葬礼演讲上观察到:“某某对人类社会的发展做出了不可磨灭的贡献…”

Best,

Jack

喜欢我的作品吗?别忘了给予支持与赞赏,让我知道在创作的路上有你陪伴,一起延续这份热忱!